What’s your name? What’s your identity?

Как Вас зовут?

Russian class was offered at our rival high school. I had to bus there and back each day and eat my lunch in transit. That didn’t deter me. The teacher was great and loved my enthusiasm for the language, totting up pages and pages of grammar homework like a champ.

Studying Russian, and being good at it, became part of my identity. On a Close-Up trip to DC, senior year, I used our half-day of free time to knock on the actual door of the actual Soviet embassy, leaving with a packet of communist tracts I carted around for decades. I went to college with the stated goal (in a bracingly ambitious essay) of becoming the Ambassador to the Soviet Union.

Tracing a circular path

Wrong turns led me away from that goal, and the Soviet Union closed up shop anyway. But still, I knew there was a job I could do that would be fulfilling, and it needed to have languages and travel in it, somehow. I pushed that rock up a hill for a decade while my parents worried. Jobs weren’t for loving, they were for providing. I tried a lot of jobs. A whole lotta jobs (here’s the list).

It took me a while, but I found my way back to international affairs, with Spanish and a graduate degree, though I’d changed my mind about working in embassies. I was in a job interview when lightning struck. I didn’t know what the job was, exactly, but I knew one thing for sure: I wanted it. It involved travel, and foreign aid, and a team of people I instantly respected.

Three little words

It took me a few months before I understood we were evaluating foreign aid – a three-word phrase I copied from a more experienced colleague, which still failed to transmit meaning to family, friends, romantic interests, and immigration officers all over the world, for pretty much the entirety of my career.

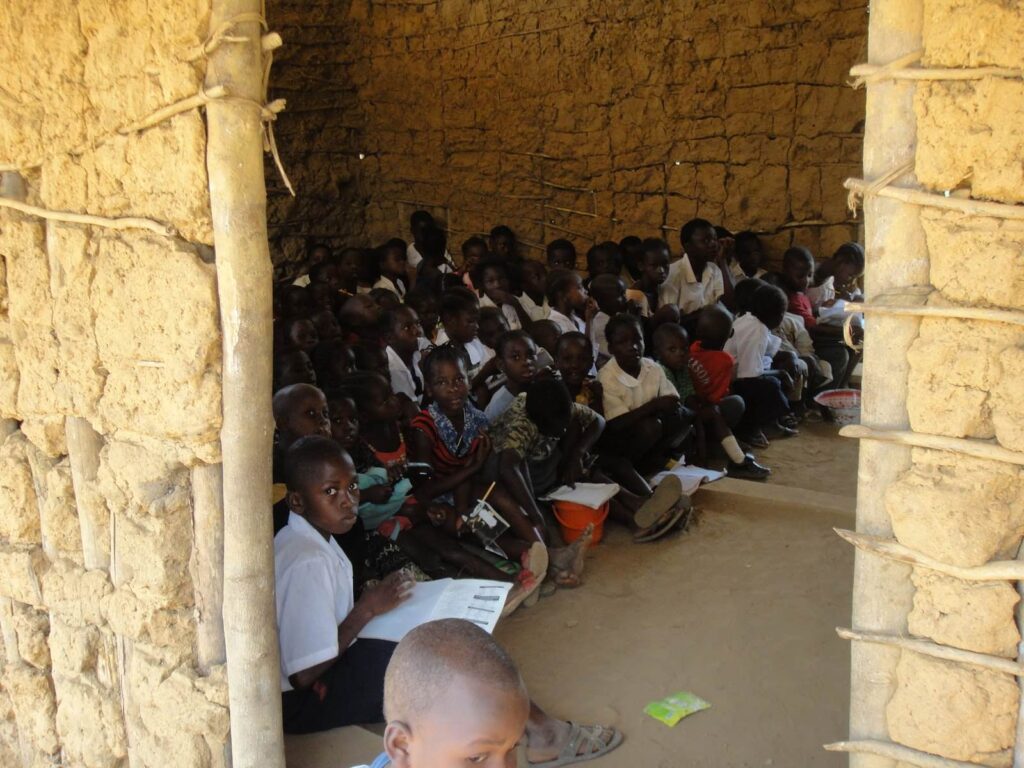

So I learned to elaborate, in a slightly larger nutshell, to say: When the U.S. or the U.N. or some non-profit does a project in a developing country, like building schools or training nurses or helping farmers, it’s my job to evaluate how well that project accomplished what it set out to do.

If my interlocutor’s eyes hadn’t glazed over by that point, I might add that I conducted surveys and focus groups to find out if the new school or the trained nurses or farmers or communities were better off because of the project, or not, and whether any improvement was worth the costs.

It’s still a big simplification. But it’s handy. And I know it’s not common knowledge that projects – even domestic ones – are regularly evaluated. Audited, maybe, but program evaluation is not well known. Evidence of that is that even I didn’t know I was doing it for the first six months of that fateful job. Soon, evaluating found a welcoming home with me. I am critical by nature, but also compassionate – a pretty good identity combination for this work.

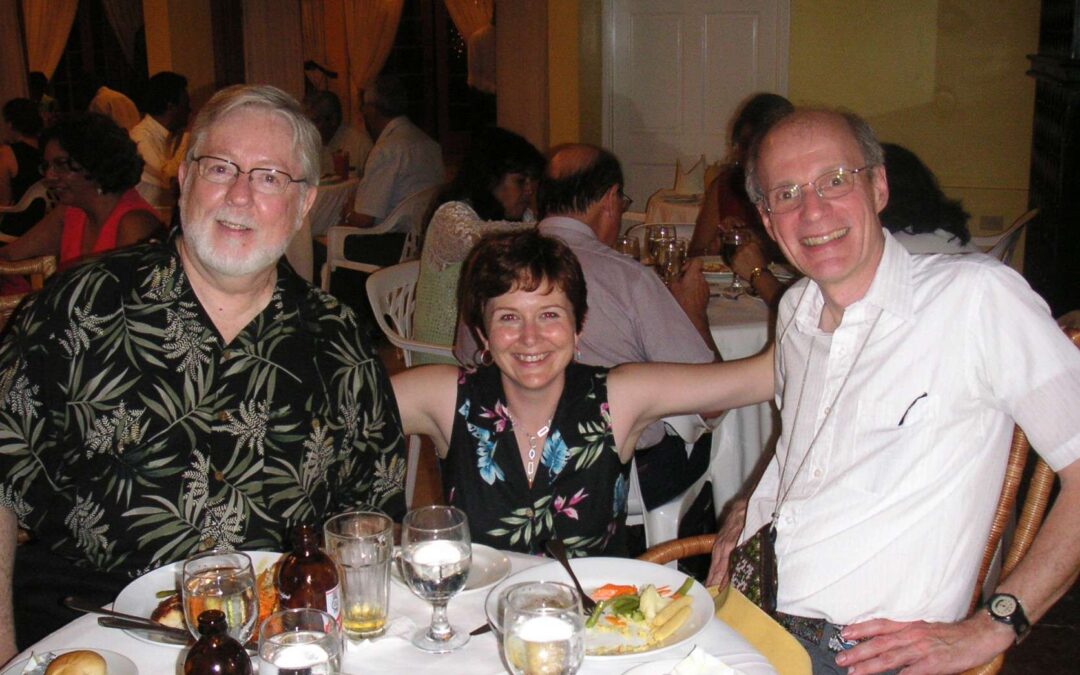

Meanwhile, a magnificent mentor/boss and a great team from that job became lifelong friends.

Not everyone finds a dream job, and when I had a minute to think about it, I knew how lucky I was. I rarely had a spare minute, though, because I was busy putting my heart and soul into it.

Blogging about work

Since 2011, I’ve been blogging for family and friends about the places I’ve visited while doing this work. My posts are mostly about that travel, and those family and friends, and some political opinions, and some creative writing.

Over time, the projects I evaluated got bigger and more complicated. I evaluated in many different sectors. I loved being busy, having deadlines, though I sometimes tried to do too much and wiped myself out. (Sorry, Ramon.) Even during COVID, I found ways to continue – like helping more junior evaluators do the job in their home countries, with some guidance to help them satisfy requirements and be taken seriously. I made a name for myself, and earlier this year I started a professional blog to talk about evaluation topics with other evaluators. Very early this year. In the “before times.”

About a week after I posted my first professional blog post, the new administration started its demolition of USAID. Most of the evaluations I did, and all the ones I was contracted for this January, were of USAID projects. Unless you live under a rock (or perhaps outside the DC Beltway?) you probably know, USAID has been gutted.

Time on my hands

Work expands to fill the time allotted. That’s a quote from Cyril Northcote Parkinson, who won the Most English Name contest in 1919 (I’m kidding). But he’s right: all my work with USAID has been cancelled, but I feel as busy as ever.

I’ve read a lot from known and unknown colleagues – USAID staff, contractors, other evaluators, local USAID staff around the world – and it’s taxing. They talk about all the things they’ve accomplished, on shoestring budgets, under various contextual constraints… and detail the difference they’ve made. Every one of them made a difference. That should be heartening but it’s painful to know their work has ended, for reasons of a ketamine-addicted gazillionaire with a chainsaw.

(Here’s a figure: his one-year salary is more than double the entire annual USAID budget. His illegal drugs, jet flights, trying to buy state elections, and bribes to his boss could alternatively be used to feed people, save them and their unborn babies from AIDS, provide vaccines a dozen other diseases like polio, monitor disease outbreaks, help governments fight corruption and become more democratic, train nurse assistants, help young entrepreneurs, etc. Tell me USAID wasn’t a bargain.)

Me, I was never going to be the one working in a refugee camp and giving vaccine shots or feeding malnourished children. Neither did I train nurse assistants, or first-time entrepreneurs, or democracy advocates in autocratic countries. My job always came later: I went back to talk to those trainees or others who had been touched by the projects. I won’t tell you exactly what they told me, because I promised them confidentiality. But I will say the projects I evaluated changed people’s lives for the better.

What went wrong?

If you’d like to hear about aid projects that wasted time or money, you’ve come to the wrong blog post. If anyone in the disgusting current administration had bothered to ask, evaluators like me would have shared our experiences and our evidence, to work together on improving outcomes. In fact, there was a massive public database of our findings, all available on the web, that DOGE erased. (Luckily, people are working to reconstruct it – and it’s still free and open to the public.)

So you can’t convince me the slimeballs in charge of our government were interested in finding and ending waste, fraud and abuse. It’s pretty obvious that, in fact, they themselves are busy wasting money, committing fraud, and abusing people, states, institutions and services in every corner of the government and society they can reach. And some they’re not supposed to reach, like judicial and inspector general oversight.

Shame on you if you think any of this is a good idea. Just because you don’t understand it doesn’t mean it should be shut down. You don’t understand neurosurgery (and neither do I), but do you want them to stop doing it when it’s necessary? You don’t understand soft power or what good it does to feed starving people in a war zone. But somehow you think you know better, even if you’d never heard of USAID three months ago?

Shame also on Fox News and its derivatives, and the pod jockeys and influencers who are all about “getting theirs” even if it means tanking democracy. Shame. If zombies were real, your own ancestors would emerge from their graves to come and vomit on your heads.

Luck and its disappearance?

I’ve learned a lot more about USAID in the past two months – the vast spread of its work, the extent of its many safeguards, the pride of its staff everywhere, including the host country staff. The work was part of their identity, as it was for me. I’m still trying to figure out who I am in the absence of this job. All of us, we were lucky to find something we loved, that also provided. We contributed to something larger than ourselves, and we’ll find ways to do that again.

And luck can run out, of course, but I don’t regret a minute of my career. I’d rather be unemployed and uncertain, than be part of the cult that backs this administration. How can I tell it’s a cult? Easy. Cults are about faith. The administration gets their faith for free, and doesn’t have to give them anything in return. Prices haven’t come down. Ukraine is still facing Russian aggression. There are no new jobs now or in any configuration of the foreseeable future. The government has spent MORE so far this year than any year in history. Instead of draining the swamp, the administration is a festering boil of corruption in every direction.

The president golfs more days than not. That’s how I can tell it’s a cult. If it weren’t, the people who voted for him would already have had his head on the chopping block. Because he’s not serving them, despite his endless promises. But they defend him even if they have to make up a reason – that’s a cult.

All I can hope is that the scales fall from their eyes.

The professional blog

If you’re reading this, you know writing is something I love, and this blog helps me get out of my head onto the page. In the new professional blog, I just wrote a post about the dismantling of USAID, from a professional angle: can we do aid better?