If you’re reading a lot of LinkedIn right now, as I am, you might think a rethink is in order. You’d be in good company.

Lauren Kaplan’s LinkedIn post titled “Rethinking Foreign Aid in Africa: Between Dependency and Development” asks a pressing question:

If U.S. foreign aid in Africa has truly been effective over the decades… then why have the immediate consequences of its pause been so catastrophic?

Lauren Kaplan, Linkedin Post

Her question stopped me cold. I have great faith in her goodwill with this question, and that of the people engaging with her post. Others (e.g., Marc Shiman, Emily Brearley, Unlock Aid, MFAN) are also posting about what they call an “opportunity” to make aid better, in the midst of this madness. Is there an opportunity? I’m an evaluator. Had you spoken with me six months ago, I would have given you a laundry list.

But why doesn’t the discussion acknowledge that reform has been part of the conversation at the highest levels of USAID and other agencies for decades? Granted, actual change can be glacial. It is only “easy” to change a bureaucracy if you’re a ketamine-fueled, empathy-deficient freak show with a chainsaw. The aid industry – like any industry – is also change-averse. In a capitalist twist on Newton’s first law, an economic object in motion stays profitably in motion unless stopped or diverted by an equal or greater moneygrab. (I’m looking at you, Starlink, and your Mars Shot too.)

But inertia is not the whole story. I’ve been thinking about issues that bear on Kaplan’s pressing question. Let’s get into it.

- Humanitarian and development aid are very different.

- Corollary: Each of those also covers an immense breadth of activities, implemented differently in vastly different contexts. Kaleidoscope, more than spectrum.

- Aid can only supplement, pilot, or catalyze – not fix broken governments or systems.

- Increased complexity tends to add bureaucracy, not alleviate it.

- Dependency is a judgement, and not necessarily a correct one, and certainly not a blanket one

Humanitarian and development aid are very different

Shuttering humanitarian aid is catastrophically cruel and deadly. Shuttering development aid is stupid and mean (in both definitions: nasty and selfish).

Proposing reform to humanitarian aid and proposing reform to development aid also differ. Answering Kaplan’s pressing question means we have to look at both, separately. I don’t think Kaplan is promoting bean-counting over saving lives: she just seems to confound development and humanitarian aid in her effort to get people to think about how to make aid better.

The pressing question asks about catastrophic consequences of demolishing aid. The catastrophes in front of us are humanitarian calamities like Sudan and Myanmar. But Kaplan references capacity strengthening, governance, and infrastructure, which are more associated with longer-chain development aid. The consequences of halting development aid are playing out – projects, staff, recipients and economies are upended – but there is at least some time and space to react before lives are lost from it. My work has been mostly on the development side, so I confess limited knowledge and experience of humanitarian aid. But I can read and see where people are losing their lives.

The line between humanitarian and development aid is not black and white, like when Kaplan mentions building community resilience and sustainability. When WFP works with displaced people, for example, they may support countries and individuals to build institutional and community resilience against future shocks. They also make sure kids get some schooling when they’re living in refugee camps. Providing HIV meds is also a longer-term strategy, but loss of life is an acute possibility for many who have lost access since the administration gutted PEPFAR. Pregnant mothers with HIV and no meds will likely pass the disease to their babies. Still, despite this blurring of the “line” between humanitarian and development aid, the loss of innocent lives means action is imperative in some cases and can be more thought-out in others. So, an opportunity, yes.

Kaleidoscopic – and hard to characterize broadly

I’ve evaluated aid projects for twenty-plus years and I was still gobsmacked reading about the thousands of projects contained in USAID’s small budget (around 0.7% of the US budget.) One way to get a handle on it is earmarks: USAID Mission priorities were ring-fenced by Congress’ goals, like food security or global health or private sector engagement. Within those goals, USAID staff researched what they could do to improve systems and outcomes in a given country or region, within their budget and staff size. One country’s USAID team might get $5m for global health, and another $10m, reflecting local needs and opportunities as well as US strategic priorities.

Now, how they chose to intervene varied immensely: by sector, funding size and type, political visibility, implementer type, target beneficiaries or participants, contract or agreement type, and other factors. The countries where USAID worked also vary by region, cultures, social, political and institutional conditions, levels of conflict, natural and human resources…

The number of permutations of aid can be conservatively estimated at…

Keri, estimating from field experience

∞.

The result is a pretty complex mix (which maybe you can infer by how many times the administration has botched even their wholesale destruction.) It is tempting for aid actors to look at the kaleidoscope and “sum up” with discussions of inefficiency and dependence. Neither Kaplan nor other people talking about reform are the only ones to do it. (The administration itself doesn’t shy away from generalizing, either, and using much worse epithets.) But generalizing even with the intent to reform misses some very useful learning. That learning can make aid better, and can support governments that want to do better.

For me, there are not a lot of helpful lessons that emerge from looking across even the development aid side, as if it’s one big, parallel effort everywhere. Of course, it’s easier to come up with reform ideas at that level of abstraction, but their condemnation is just too general.

(Which relates to another issue aid has always had – how does USAID roll up all these small successes to tell their story better? The answer, for me, is – you don’t. But that, too, is a discussion for a later post.)

Aid’s impact, in context

Aid is not, has never been, and could never be enough on its own to make the deep and long-lasting changes Kaplan suggests in her pressing question. In humanitarian work, the goals are immediate and life-saving, with some attempt to attend to resilience and sustainability (as Kaplan also notes) but in the end, with tight budgets and bombs dropping all around – so, pretty narrow.

I say “Sudan” and “Myanmar” and readers may be imagining “The Other” – masses of (often) black and brown people in poor, far-off places, whose fates we in the developed world rarely share. The U.S. could express sympathy and “solidarity”, and we could send aid, or not. We could ignore them – they’re not our problem, some say. But what we seem to do in any case, almost reflexively, is make them “the other”.

But, in reality, almost any country in the world could require such help from external sources, especially as climate catastrophes become more frequent. If we play a little thought experiment, we could end up thinking about a different pressing question. Imagine Mexico supporting the U.S. in the event of a hurricane: there would be no expectation that Mexico’s assistance should fundamentally alter U.S. institutions or economic structure or power relationships. It’s goodwill, it’s recognition of human suffering and the ability to help, it’s soft power. It might be something like, “My country is close and didn’t get hit by the hurricane, so our Navy hospital ship can arrive faster. Consider it done.” This story strips out the value judgements we have about “poor countries”, and makes Kaplan’s question seem to have a subterranean clause: “Why can’t/don’t countries in development deal with their own humanitarian crises?”

I would argue there’s serious “othering” going on, but when I try to stand outside that tendency and ask why Global South countries struggle governmentally, financially, economically, and institutionally, it’s not hard to imagine why:

- The legacy of colonialism (I’m no expert so I won’t try to describe this, but acting like it’s not there doesn’t make it go away, either).

- Resource wealth but extractive commercial relationships (with rapacious effects on environment and, then, climate). This is not just the past, but also visible in high-interest loans from the IMF, World Bank, or China.

- Conflict and whether democracy and resources reach everyone, as the poorest countries are also the most rural.

- Deep poverty traps “due to food insecurity, poor infrastructure, lack of access to education and health services, or geographical and environmental challenges.” [Thanks to Jeffrey Sachs for this list.]

The way we do capitalism

Self-sufficiency and economic sovereignty are goals for any nation, though the degree to which this is rhetorical versus concretely, conscientiously and wisely pursued varies. It’s past time for me to read Dead Aid (not to mention Kaplan’s other sources, which, as I’m newly unemployed, I have time to canvass) – but for now I’ll just ask if economic sovereignty is enough, on its own, for the people in those countries to rise out of poverty. I think it’s fair to question how economic “sovereignty” comes about and how well it would hold up across populations living in poverty or extreme poverty, who may have few democratic levers to ensure fair play.

Because I don’t believe that capitalism unchecked, capitalism without social protection, capitalism without civil society guardrails, has as its central goal bringing people out of poverty. If it happens, as a corollary to economic development, some politician will probably credit capitalism with making it happen. But the raw goal of capitalism is money-making. In my own country right now, I see how Trump-voting capitalists would throw wide swaths of the population under the poverty bus if they can have fewer regulations, fewer taxes, more freedom to monopolize, and greater profit. Every country, every society, has to make and remake these calculations for itself. But one thing that development aid does that capitalism does not do, and that some countries do not do, is direct some creative spending toward at least some populations where the deprivations of poverty strike the worst. You can call that dependency, but I for one am still on-side.

Is a country dependent if it accepts aid?

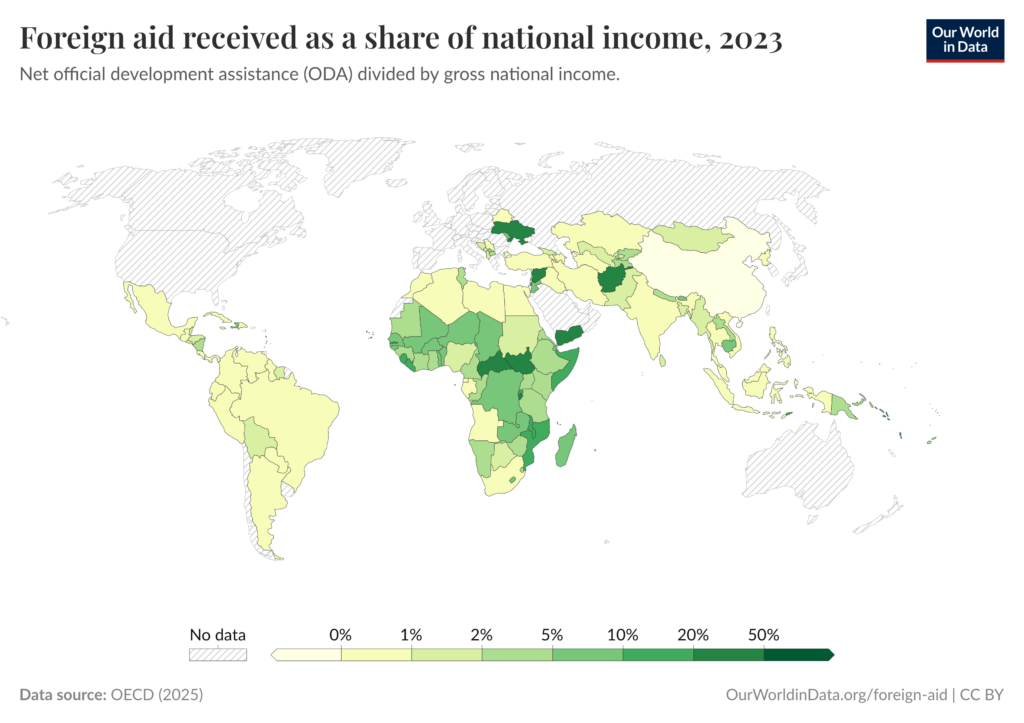

There are countries where aid was more than a smidgen of their overall income, like Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Yemen, Syria, South Sudan, Ukraine and Somalia. (The graph below defines aid as non-military support for “economic development and welfare… either a grant or a loan with favorable terms.”) One big thing many of these countries have in common is war, and another is very, very low income per capita: as low as $400-$500 per person, per year. Aid is not evenly dispensed based on this, but this handful of countries also has strategic interest – as does Ukraine, which also received aid in 2023 that totaled a big chunk of their budget.

Most countries receive budget help at much lower levels, like one to ten percent of their country’s income. (Pay attention to that legend: it is not evenly spaced. The difference from 1 to 2% is the same size as the difference between 20 to 50%. That makes the aid percentages appear larger than they are.) The aid headed to low-income and lower-middle income countries on, say, education issues was a minuscule fraction of what the countries themselves spent on their own education ministries. So “dependency” is quite imprecise, if not simply wrong, in implying that these countries wouldn’t be doing much at all without bags of cash and teams of know-it-all consultants from aid agencies.

Should aid be expected to have systemic impacts? Across the evaluations I’ve carried out, development aid was supposed to be catalytic, boosting a statistical office in an education ministry, for example, not systemic – creating or overhauling the whole ministry, say. USAID seemed to understand that difference, and collaborated on politico-institutional levels to deepen the impacts of programs and projects that are only pilot-sized, demonstration-level efforts. Sure, they’d like to see some systems overhauls, but the money was never there for that, and even the most ambitious-minded aid staffers and implementers don’t claim such things.

Constellations of support

A country is in conflict; innocent people are suffering and aid provides food, water, shelter as they flee.

Another country signs peace accords; aid helps rebuild civil society and press freedoms and get concessions from resource extractors with conditions slightly more favorable to the populace.

Another country has brighter prospects but persistent low growth; aid arrives with workforce training and access to credit for entrepreneurs, or support for rural health services and farmers and food safety testing, for example.

In other words, there is a great deal of thoughtfulness and complementarity to what aid does. The way some people talk about it, aid is flying over Zambia dropping bags of cash. Aid functionaries identify pressing issues and help countries address them, all in a context of addressing the US’s best interests. Wasn’t Reagan famous for the quote that a rising tide raises all boats? With a small relative investment spread thinly across several thousand tiny programs, any fractional poor expenditures do not erase the good that aid accomplished. (That would be a very interesting generalization to try to quantify. Another post, perhaps.)

And aid was at least as much benefit to the U.S. as it was to the countries it meant to help. This was by design, because there’s no substantial natural constituency inside the U.S. to preserve these expenditures if they’re not getting something out of it. (I might be helping make Kaplan’s point here, or an adjacent one, but then again, I am engaging because she’s clearly thinking about this for good reasons. So I’ll press on.) Food aid is a great example. U.S. farmers sold $2 billion in food to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, for use in emergencies and development projects overseas. A fraction – something around $160 million over various budget years – went to buying food locally or regionally for those emergency and development purposes, even though that is much more efficient than shipping it. Why?

Because Big Agriculture is powerful and has lobbyists, that’s why. Because U.S. shipping companies (and their lobbyists) wrote it into the law that food aid must go via US merchant marine ships, even though a Liberian-flagged ship would save money. And because even cold logic – time and cost – cannot convince the American people to spend $2 billion on food aid unless there’s a direct benefit to Americans. One might conclude that this is a wasteful, corrupt system, or that the powerful voices in the halls of power struck a balance that feeds people, even if looking inside the sausage factory makes us queasy.

A recently leaked memo (reported by Sara Jarvis for Devex in this March, 20th article), reportedly from the administration, said that future aid efforts should “’not be philanthropic in nature’ but result in ‘first-order benefits’ to Americans back home, project ‘America’s soft power,’ enhances national security, commercial interests, and counters global competitors, such as China.” But as just one food aid example illustrates, American aid was already doing that. They killed it so they could say they’d do something better.

Old school influence

One thing that is certain is that aid is a way to wield and gain influence. It’s not necessarily pretty – another sausage analogy here – but that doesn’t mean the US is better off jettisoning that influence. Jeffrey Gettleman called it a “steady erosion of support” – where once we could count on Kenya or Bangladesh or Guatemala to vote with us on a UN resolution, or allow our businesspeople to come in and sell American goods, our influence is now in the red. Countries with worsening human development, health, education and other index figures are also in danger, and that puts the US and other wealthy countries in danger: more poverty, more migration, more unemployment, more economies in crisis, more rebellion. Especially as the administration cut aid arbitrarily and across the board. The future looks increasingly bleak for all of us.

The Jarvis article about the memo leaked in March quoted the memo as saying, “Foreign aid should ‘provide geopolitical leverage for the President on the global chess board.'” And also: “These efforts can foster stability in volatile regions and prevent conditions that breed extremism and terrorism.” This, from someone reportedly within the administration, shows that even the administration recognizes the value of influence, the value of soft power. They just want to give the spoils to others.

However, even this leaked memo appears already to have been superseded by draconian cuts at State, which in turn has been superseded by a new Executive Order to zero out ALL engagement in Africa. And the U.S. says it’s going to pull out of negotiations for the end of the war in Ukraine, so they can cut that budget line too. Marco Rubio is no more than the State Department’s Flat Stanley, a cardboard cut-out the administration puts at a podium for a photo shoot and then mails somewhere else.

Aid’s giant, well-coordinated, linear plan

I’m not saying aid was all a giant, well-coordinated, linear plan: humanitarian aid till they can stand on their feet in peace, development aid to stand them up tall, then a happy graduation day. Would that it worked with such clarity and step-wise logic. (Rubio, in his infinite idiocy, thinks it works pretty much like that: “The best foreign aid is foreign aid that ultimately ends because it’s successful, because you go in, you help somebody, they build up their capacity, and now they can handle it themselves, and they don’t need foreign aid anymore.”) Yes, puppet, that’s how it works. Give a country six months, they should have it down pat. *drops forehead to desk, not for the first time this week*

USAID had elements of well-coordinated planning, and elements of chaos, and elements of leaping quickly to respond, and elements of being caught on the back foot, and elements of failure, and elements of all the things Kaplan and her fellow authors and thinkers decry. The Jarvis article cites the leaked plan author as writing, “the U.S. international assistance apparatus has lacked discipline and strategic alignment; is inefficient and fragmented; and is a “tangled web of overlapping mandates, chronic mission creep, and Congressional micromanagement.’ It said it created an ‘incoherent portfolio of programs” that were “implemented by organizations that represent a wide array of motivations and interests.'”

The truth is in some non-existent, non-ideological space between “giant, well-coordinated linear plan” and “tangled web of overlapping mandates.”

I will also point out again that people have been thinking about aid, and trying to do it and do it better, to be more organized, to reduce bureaucracy, to improve impact and to measure it better, all along. These commentaries, the books in Kaplan’s post, her pressing question, and my own critiques as an evaluator, are part of a long history of challenging the status quo. The only thing new the muskrat has brought to this effort is scope, brutality, and a fanatical aversion to thoughtfulness.

No one gets into aid work thinking they want to make countries dependent on it. (Well, maybe the big engineering firms buying up smaller companies working in development… yeah, that’s for another post.) It’s worthwhile to discuss whether, inadvertently, the effect the aid industry has had. But I repeat: 1) we’re not the first people to discuss this; 2) aid is extraordinarily varied and as such could be building a dependency in one situation but not in many others (or vice versa); 3) as with the debates on welfare in the U.S. in the 80s and 90s, dependency is a moniker with a lot of baggage.

Easy answers? Wait, I know this one

The kaleidoscopic variation makes an easy or easier answer all the more desirable. The leaked new plan for USAID made clear they were going to find an easier answer. Here’s a quote from a March 19th Nahal Toosi and Daniel Lippman article in Politico on the topic:

The proposal says existing U.S. aid and development programming is “inefficient and fragmented” and made the mistake of engaging “in every sector in every country,” with questionable results at best.

A better approach, the plan says, would be to “foster peace and stability in regions critical to U.S. interests, catalyze economic opportunities that support American businesses and consumers, and mitigate global threats such as pandemic diseases.”

Of course, that’s what USAID already does. What USAID did.

The article goes on to quote the leaked plan’s masterful creativity in proposing innovation for aid: “The proposal stresses that aid programs should have end dates and their success measured carefully. Among other ideas, it suggests using blockchain technology to help track funds and ensure accountability.”

For heaven’s sake. What nonsense.

Keri, restraining F-Bombs like a boss

Every USAID project ever has had an end date – shockingly short-term end dates, in most cases. And anyone who worked with USAID from any angle at any time in any country in any sector knows: project success is measured meticulously, even obsessively. There’s more scrutiny and more scrupulous monitoring of USAID projects than in just about anything else the U.S. government does – certainly much more than agencies and activities that consume multiples of USAID’s budget, like defense, social security, or health care. And blockchain? Pardon me if I see that as just a plug that Certain People in Power with Big Investments in the Sector are pushing. USAID scrutinized budgets to the penny constantly and consistently. Arguments can be made about spending priorities, but protecting the disbursement with blockchain would only add risk that someone would lose their password.

The current leaders at State think they can do all this so simply, cleanly, un-bureaucratically. I say “HA!” As I wrote in this previous post on complexity, we are talking about wicked problems here – governance and corruption challenges, chronically low-performing economies with natural resources but little value-add, low participation of women, youth and minorities in the work force, and a slew more systemic issues. And despite big talk at State about “tangled” and “overlapping” programming, they will do the same thing. People “pick complex solutions over simple ones, additive solutions rather than subtracting or right-sizing or other functions. So cooperation projects themselves, and funding agencies, are often adding to complexity.” Every added layer of complexity also adds a layer of bureaucracy.

Even the current overlords are all gung-ho about cutting the federal workforce but have you noticed how many staff members DOGE has had to bring on? Turns out even a woodchipper needs a lot of hands on deck!

Keri, snarky aside

So New, That Mandate of Yours

Another article, reported by Adva Saldinger and Elissa Miolene for Devex, cites the leaked proposal to report that the proposed new humanitarian office at State would “have a mandate of saving lives, the memo read, and its success would be measured by “concrete metrics” like disease containment, famine aversion, and lives saved.” Right, because the Bureau of Humanitarian Affairs didn’t have that mandate or use any of those metrics? Do these mooyuks actually believe their own propaganda? That article continues, pointing to the ways USAID or other aid bodies like DFC and MCC have been using the same methods and tactics discussed in the leaked plan. But the memo was just as derivative about “more prosperous” and “stronger” as it was about “safer,” so just roll your eyes with me and we’ll move on.

They speak as if USAID staff had not grappled with “the tangle” and the complexity; never looked for clear upstream messages and themes; and never considered clear goals and line of sight to outcomes and impacts. If any humanitarian or other aid work happens under the $28 billion the administration seems to want to allot to State, they’re going to have as hard a time as USAID has always had once they get into the weeds. Well, with that budget they might be okay, since they won’t be able to do very much.

It’s really not a new mandate

I’m sorry to say that I don’t find Kaplan’s suggested focus areas any more “new” or “real”, however, than what the memo described. She provided the following bulleted list, saying that “some argue that ‘real’ progress requires:

- ✅ Investment-driven growth: shifting the focus from external aid to private sector investment, entrepreneurship, and trade partnerships.

- ✅ Stronger governance and institutions: ensuring that economic policies promote transparency, accountability, and long-term stability.

- ✅ Infrastructure and innovation: building energy, transport, and digital infrastructure that enables sustainable development.

- ✅ Economic diversification: moving beyond raw material exports to industries that add value and create local wealth.”

But if you look at USAID (and other agencies, for that matter), this is almost exactly the wishlist they have been aiming for, increasingly over the last two decades. Diversification has been part of the discussion for even longer. I, Keri Culver, personally and with documentary proof, have evaluated projects that fit neatly into each of these green checkmarks. Wanna see the reports? And it’s not that I am on the cutting edge of aid project evaluation: it’s that this is what is out there to be evaluated.

Here’s another reform I’ve watched play out over the course of my evaluating career: receiving country institutions have much more voice in what kinds of interventions USAID implements. Not every project has this characteristic, it’s imperfectly applied, and being the “donor” will always confer power, so this reform is really more of a compromise. But that it’s noticeable across projects means that USAID has made a concerted effort to work better with their partners. If you did a search for the phrase “demand-driven” on USAID’s reports website (the “DEC”), and graphed the results, you’d see it laid out in black and white. (Of course, the administration shut down the DEC, avoiding the accountability they say USAID lacked. Another post, I guess.)

So when I read about “aid reform”, right now, even with the impressive syllabus and the earnest good will, the arguments don’t square with what I know about where USAID was on January 19, 2025. I welcome this conversation and I hope I’m contributing to it constructively, but we have to talk about where aid really is before we start echoing the administration’s false claims and aiming in what feels like a circular firing squad.

Ego-bound and down

You can see from the photo below how happy I am, in Russia in 2004, early in my evaluation career. I imagine there’s something else in my smile: pride. I hadn’t had that before I found evaluation as a career, despite looking high and low. (See my personal blog for a post on this search. If I do say so myself, that’s a helluva list of jobs over the years. I guarantee my smile never looked this proud when I worked as a waitress at The Kettle in Midland, Texas. If, indeed, I smiled at all.)

Pride in your work is good, and it can also have a selfish or defensive side, where you identify a little too hard with something that isn’t entirely of your own doing. This train of thought has been on my front burner a lot these days. I identify a lot with my profession, in a good way for sure, and like others I have my blind spots. It’s pleasant to think being an evaluator has taught me to step outside a situation and look at it from other perspectives. But no human is fully objective or fully capable of setting down their ego.

Setting it down, though, is a laudable goal. It’s something we have to keep trying to do, over and over again, because the ego is always going to be there, whispering to us about how much we know and how much we can help, if people would just follow our advice. I’m not sure how to resolve this writ large, but part of the answer could be a shared rethink about localization, bureaucracy reform, changing priorities, or other potential improvements for aid. I don’t think the current discussion I’ve seen has moved that needle, though.

More hubris? Oh yeah, it’s all over the place

We also have to face something ugly: nothing about this discussion has affected (or likely will affect) the current US administration’s plans. They’ve undercut even their own leaked memo, and then an even newer plan acts as if Africa doesn’t exist. Our rethink is an intellectual exercise, not reform. And whether we rethink what we are doing or not, recipient countries’ own perceptions about what constitutes dependency are more important to me than a generalized pronouncement. Because I find there’s another kind of hubris in these discussions, that we, the West, with our wealth and our braniacs consulting and implementing and trying to run the show, get to decide who’s dependent and who isn’t.

If we take my points above as somewhat valuable (i.e., (1) aid is infinitely variable by program and place, (2) humanitarian aid could be needed anywhere and increasingly everywhere, (3) aid targets have evolved to include collaborative and localized work with and on governments and economies, and (4) aid is a small fraction of governments’ own spending), then a blanket statement about dependency is pompous, inaccurate, or at least a massive overstatement. I believe we risk turning these human beings and their institutions and communities and countries into “The Other” in a way that makes us feel superior. In fact our wealthier countries established, built, and benefited from their underdevelopment.

It’s neither coincidental nor ironic that Kaplan and some of the authors she cites also recognize this hubris and are lobbying for a better way – where underdeveloped countries are not dependent and decide their own fate. I think critics of dependency believe that aid as an action is inherently “othering.” That by suggesting “we” have answers “they” need, we’ve already begun to look down on them. They have a point, and yet, I have seen people from the “West” and the “Global South” (man, that has never made sense) working as equals to resolve problems we recognize together. I wish we were still doing it, flawed as we were.

I bet Kaplan and I and other concerned thinkers would have many more agreements than disagreements if we met in person and discussed these issues. Where I diverge is in saying that, since we can’t ignore who is suffering right now, and the West’s relative wealth means we can help, we should.

Let’s keep talking. (Good grief, if you’ve read this far, we should be talking about a book contract.)