I don’t know about the rest of you, but I need a break from the destruction of USAID in real time. It’s been a very long few weeks since the new U.S. administration decided to stop all aid work. Like many of you, I am out of work and scrambling to find something new. Still, when I sit down to write, I have a lot to say about a range of themes in evaluation, so I’m going to keep writing this new blog. Happy to continue the conversation about something more productive than *waves hands wildly* this horrific administration.

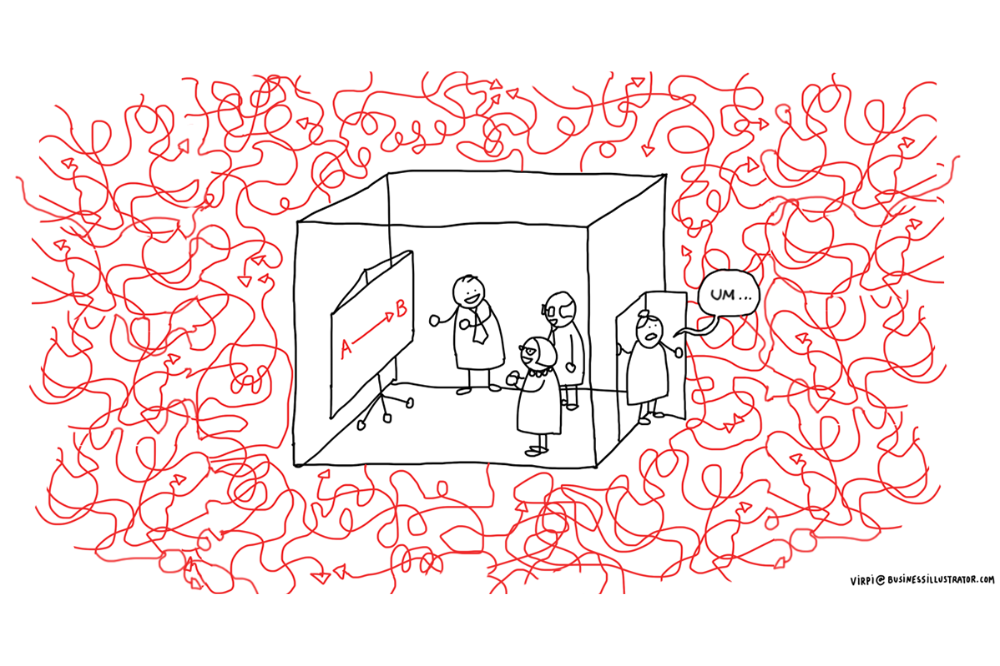

Development practitioners don’t have it easy. The changing nature of cooperation projects means that uncertainty is greater, politics require constant navigation, and the wicked problems they’re facing have no single, clear, or stable resolution. To evaluate these kinds of projects, evaluators are neck-deep in the complexity and challenges, too. Implementers have to convince aid funders that they can and will resolve development challenges. Evaluators must speak truth to power about the lack of evidence to support such results.

Why are development projects more complex? One pat answer is that, collectively, humanity has already solved the easy problems. Another part of it is that, over time, we tend toward complexity instead of simplicity. People in different experiments pick complex solutions over simple ones, additive solutions rather than subtracting or right-sizing or other functions. So cooperation projects themselves, and funding agencies, are often adding to complexity.

Wicked problems

“A class of social system problems which are ill-formulated, where the information is confusing, where there are many clients and decision-makers with conflicting values, and where the ramifications in the whole system are thoroughly confusing.”

– Horst Rittel

That’s a pretty depressing definition of wicked problems – and not very proactive. But it reflects how development challenges are nebulously interconnected and notoriously difficult to disentangle. The multiple perspectives probably conflict. Resolving issues involves difficult processes like institutional change, behavioral change, policy reform, and shifting complex economic relationships.

Development interventions designed to address the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) often include more than one of these. They might address climate change, pollution in water and soil and air, gender equality, or poverty. Other development agencies work on smaller slivers of the SDGs, like improving the business enabling environment (which requires Customs policy and regulatory reforms) so that more entrepreneurs, including small ones and new ones, decide to export their goods (which means changing the economic calculus in a given economy). An intervention might bring diversity, equity and inclusion into institutional or organizational cultures, or reform government land titling. These are all examples of complex problems that projects cannot easily fix, and evaluators can’t easily measure.

If it were easy to fix, it would have been fixed already

Development projects have multiple stakeholders with competing interests and incentives, and exogenous factors like conflicts, economic shocks, or even just a scheduled election, that add game-changing uncertainty. Development implementers develop theories of change (TOCs) but their quality varies. Many are insufficiently grounded in dynamic cultural, behavioral or institutional environments where they will be working. Often, theories of change are built at the outset of a project but not updated to reflect emergent reality over the three- to seven-year project timelines. They’re also often very high level, when the devil is in the details at the level of individual interventions.

Evaluators face these challenges too. Evaluators examine those TOCs before, during and after implementation, and provide insight on successes and challenges. One point about wicked problems is especially helpful to think about here: their solutions are not “yes and no” but “more and less”. This means that rather than documenting solutions that “work”, evaluators need to be able to talk about which configurations of actions and conditions made things somewhat better, and which configurations made things somewhat worse.

Foreign assistance is no magic bullet

As evaluators, we need to think in these terms because interventions alone cannot resolve the wicked problems. Instead, interventions combine with collaboration (or lack of it) from partner actors, interact with context, and respond to incentives. And all of these have to converge over time, and across space. Interventions often with multiple sites like school districts, health clinics, chambers of commerce, or other “units of analysis,” where conditions might be met partially but differently in each place.

Agencies, implementers, governments and academics are clamoring to see what works, what doesn’t, and why. And they want clear answers, often with the hope of adapting successful solutions used in one country or region and applying them elsewhere. Stepping into this environment as evaluators means we have to be ready to speak convincingly about what evaluation can and can’t “prove”. There are limits to “rigor” and it’s essential to address these issues frankly with evaluation commissioners. Without these discussions, we risk fooling ourselves and development partners about how to use evaluation results.