And it’s only Wednesday. It has felt like the world was on fire.

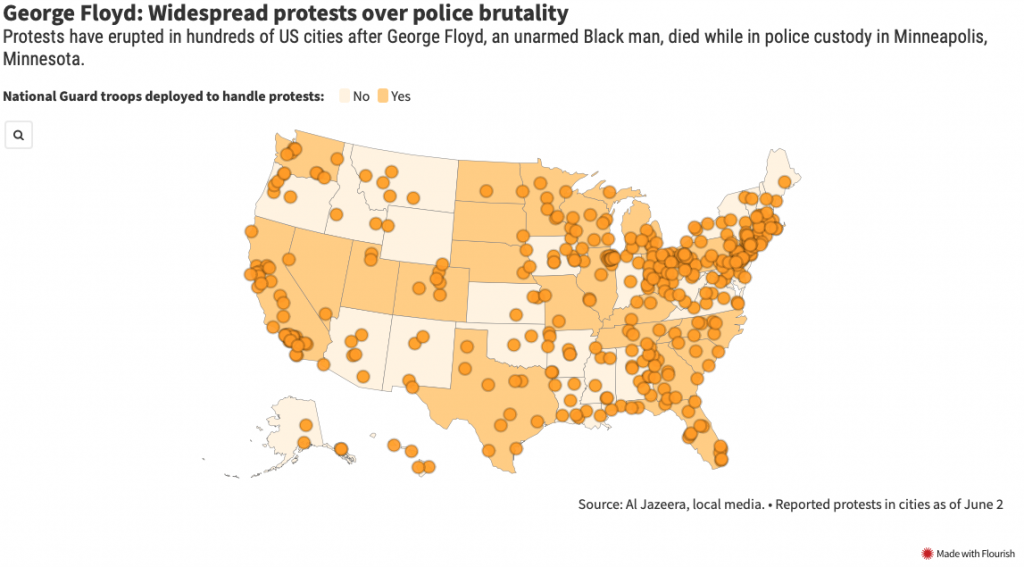

George Floyd’s murder is a horrifying testament to not having made much damn progress. I’m in awe of people protesting all over our country to say, “No. No more.” And this, in the face of the pandemic, is all the more brave, if not outright crazy. The whole country took to the streets – see the map below. This includes Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and many protests in other countries.

People in other countries have no direct relationship to this case – why would they protest a police crime (or the history of police crimes) against Black people in the U.S.? Why are French, English, Irish, Danish, German, Italian, Brazilian, Mexican, Canadian, Polish, New Zealander, and Australian people out in the streets? Even Syrians??? You’d think they had their hands quite full – but they took time to recognize George Floyd too.

They may well recognize some of the same, twisted, racist actions in George Floyd’s death as in their own countries. They may be nobly responding to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famous statement that “A threat to justice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” They may be altruistic lefty bleeding hearts.

All of those things may be true, but there’s also something special about what the United States of America is supposed to mean. Expectations for the U.S. have always been high – both within and outside our borders. We have a lot of high-level rhetoric about freedom, our grand experiment, our “City on a Hill” – from the time of our founding.

When that vision – those expectations – that rhetoric – crashes down in reality, it’s soul-crushing. And for African-Americans, often life-crushing as well.

There’s an argument to be made for the notion that people of color, particularly African-Americans, are the real “Americans” – the most in accord with that rhetoric, the ones who have most fought for it, the ones who have suffered the lack of it most painfully. (Thank you to Nikole Hannah-Jones, who wrote the brilliant, well-researched article on this that I’ve linked at the word “argument” above. Even if you leave this post, read her article.)

(Before I go on, I need to mention the issue of calling our country America as if there were no other “Americans” in this hemisphere, when in fact the most remote rural Bolivian village of Quechua-speaking farmers, the icy polar bear feeding grounds of Canada, and the ruling elite of Venezuela in Caracas are all as American as downtown Cleveland. I’ll put “America” in quotes to indicate we should not forget this.)

Hallmarks of being “American”

If all you did – through no action of your own – was get born white in a place where economics, politics, institutions, education, health, commerce, and just about everything else was designed for you and tilted against everyone else, how “American” are you? How much do you live up to our ideals? How much have you sacrificed or given or even cared? A great mass of white U.S. citizens don’t know anything about civics, have to be dragged to vote, and/or wouldn’t know marginalization or existential threat if it bit them in the ass. What do you have to be so damn proud of, if all you did was emerge into privilege?

So, in that version of being “American”, are complacency and ignorance the hallmarks? Or is it gun-toting? That certainly has a (well-funded) bandwagon to jump on. Maybe it’s fireworks? Pie? What does “American” mean, if it doesn’t mean YOU DON’T KNEEL ON SOMEONE’S NECK UNTIL HE’S DEAD? (This seems a very low bar. Isn’t this a given?)

So what does it mean to be “American”? Being pro- freedom from tyranny? Well, that doesn’t exclude anyone – even tyrants hate tyranny, they just think it’s someone else who’s doing it. You can also find whatever virtues or values we might say we “Americans” have in Johannesburg, Mumbai, Port-Au-Prince and Osaka, so they’re not “American” as much as they are universal virtues and values we all strive for.

Spending a lot of time outside the U.S., it is clear to me that what’s unique about my country is my personal experience of it, and the part of that experience that you share with your countrypeople. Like watching All in the Family on Saturday nights. Mourning the Challenger space shuttle crew. Eating pop rocks, or having a snowball fight in the yard. Reading about Abraham Lincoln from a young age and wishing you could go back in time to stop John Wilkes Booth, and help get rid of slavery.

See where it already starts to fall apart there? There are adherents of the confederacy who disagree with that whole last sentence.

The value of a melting pot

So what is it that we can be proud of, what is it that makes us unique or at least special? It’s the melting pot, the salad bowl: our country is an amalgamation of people whose roots reach back all over the world striving to make a living, raise kids, create, work, have a safe life, agree to disagree – peacefully, choose our own leaders, and not act like assholes around the world. It’s the one piece of U.S. lore I can really grab onto, that we really share.

When it works, it’s truly an accomplishment – it’s rare in human history, it’s positive, it’s mind-opening, it’s something to be proud of. Nobody dies or suffers because of it – being a salad bowl actually lifts people up, opens their minds, lets them be themselves and create and leave the world better than they found it. That makes the melting pot sacred.

My family has English and Irish roots; our ancestors came here and made lives that were difficult but presumably less oppressed than they had been in the Old World. But not everyone got here of their own free will. Slavers shoved 12.5 million people into the hulls of ships to go to the “New World”; over two million of these people died along the way; and 10 million arrived to become slaves all over the Americas. No matter the problems in Africa at the time, slavery was infinitely worse than the lives they left.

So many currents – trickles and flows and gushes and tidal waves – of people have come to the U.S. and made it home. Africans who were enslaved and brought to the U.S. have also, despite all odds and all the hatred and violence directed at them, made the U.S. home too. Miraculously, beautifully, we have melded together into one country. When we as “Americans” get along among us, that is exceptional, that is noteworthy, that is beautiful and something to be proud of. And in the case of Black Americans and others of color, it’s a particular accomplishment – because they have had to fight for it against horrifying roadblocks put up by white mainstream institutions and individuals at every single step along the way. It is a miracle that within such a system we still do meld together, we do love each other, we share friendships and companies and families and hobbies and abhorrence of racism.

James Baldwin: “We’ve got to be as clear-headed about human beings as possible, because we are still each other’s only hope.”

So I think those global folks protesting in solidarity with U.S. protesters are on to something true and somewhat hidden. They know that what is universal – humanity – isn’t nation-based. It’s not our reputation as a freedom-from-tyranny kind of place where you can have any gun you want that brought them to the streets to protest in solidarity. It’s that we are, (sometimes better than others, and still learning how to do it, far from perfect) multicultural, diverse, caring about each other across our roots and other potential divisors. The folks protesting for us in all those other countries are protesting what those asshole cops did to George Floyd, but they’re also cheering us on our journey to being better at this essential virtue that – if we’re lucky – can be applied to these United States.

It’s our job to keep doing it, do it right, get better when we don’t do it right, and be willing to learn.

Just saw this story and wanted to link to it: the Tennessee National Guard laid down their shields at a protest, in solidarity with the protesters. It’s not the only time the uniforms have expressed solidarity during these protests – they’re good examples of what getting along looks like.